How Hackensack Mountain Got Its Name

Hackensack Mountain is a rocky hill overlooking the hamlet of Warrensburg that presents an easy hike of less than one mile to its summit, which provides views of the southern Adirondacks from several open rock ledges along its ridgeline. Rising at 1,357 feet, one can catch views of mountains such as Pine, Bald, The Three Sisters, Hadley, Baldhead, Moose, Number Nine, and Crane, and the hamlet of Warrensburg, below. The trail system on Hackensack can be accessed from two trailheads: one at the end of Hackensack Avenue, and the other off Prospect Street. For a trail map with mileages denoted on the trail segments, see: https://public.warrencountyny.gov/gis/maps/Hackensack%20Mt%20-%20Warrensburg.pdf

A History of the Name

The origin of the name of the peak is a bit complicated and uncertain. According to the Warrensburg Town Historian, the name “Hackensack” is derived from the Algonquin term Achkincheschakey (A-kin-hes-kakee), which means “where two rivers come together.” William M. Beauchamp in his classic work, Aboriginal Place Names of New York, elaborates further:

“Hackensack; town in Bergen County, New Jersey. An Indian word; authorities differ as to its meaning, the many versions being ‘hook mouth,’ ‘stream that unites with another on low ground,’ ‘on low ground,’ ‘land of the big snake.’”

As to the “hook mouth” version, J. Hammond Trumbull states in his 1870 work, The Composition of Indian Geographical names, Illustrated from the Algonkin Languages:

“Hackensack may have had its name from the húcquan-sauk, 'hook mouth,' by which the waters of Newark Bay find their way, around Bergen Point, by the Kill van Cul, to New York Bay.”

Finally, Joshua Jelly-Schapiro in his book, Names of New York, says the name “Achkincheschakey” is a Munsee term for a “stream which discharges itself into another on the level ground.” The Munsee are a subtribe and one of the three divisions of the Lenape Indians who once lived along the upper portion of the Delaware River and other regions of southern New York as well as New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Trumbell refers to the Hackensacks as a sub-tribe of the Lenape. The Encyclopedia of New Jersey Indians provides some clarification, noting that the Hackensacks were comprised of several Munsee Delaware-speaking groups which inhabited the coastal lowlands of northeastern New Jersey. The Delaware, who called themselves the Lenni-Lenape (or Lenape), are an Algonquian-speaking group whom the Algonquian peoples along the East Coast considered the “grandfathers” from whom all Algonquian-speaking peoples originated.

Portion of the 1895 USGS North Creek quadrangle map, where Hackensack is incorrectly spelled "Hackenback." (Source: US Geological Survey, topoView, https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/topoview/viewer)

Lucien R. Burleigh's lithograph of Warrensburgh, N.Y. from 1891, with Hackensack Mountain shown in the back. (Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3804w.pm006490/?r=-0.122,0.056,1.191,0.646,0)

When folks hear of Hackensack, they think of the city which is the county seat of Bergen County, New Jersey. For more information on the Hackensack tribe and their relationship to Bergen County, see Kevin W. Wright’s essay, “Native Americans in Bergen County,” Barbara Gooding et al’s Hackensack, and Francis A. Westervelt’s History of Bergen County, New Jersey: 1630-1923.

Hackensack Mountain is near the confluence of the Schroon and Hudson Rivers, but whether it acquired its name through Native Americans due to this geographical fact is not certain. Warrensburg is quite a distance north of the territory occupied by the Lenapes. Whether it was coined on or prior to 1871 by a resident of Warrensburg who hailed from Bergen County is unclear, as no historical record pertaining to such a person (such as a census record) has been found.

As for the variations of the name “Hackensack,” below is a collection of such as taken from Frank W. Hodge’s Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico and Patricia R. Clark’s Tribal Names of the Americas:

achkincheschakey | hacansacke | hackingkescaky

achkingkesacky | haccinsack | hackingsack

achkingkesaky | hachinghsack | hackinkasacky

achkinkehacky | hachkinkeshaky | hackinkesackingh

achkinkes hacky | hackinckesaky | hackinkesackinghs

achkinkeshacky | hackinghesaky | hackinkesacky

achkinkeshaky | hackinghsack | hackinkesaky

ackinckesacky | hackinghsackin | hackinsack

ackkinkashacky | hackinghsakij | hackinsagh

ackkinkas-hacky | hackingkesacky | hacquinsack

a-kin-hes-kakee |

The earliest reference to the name of the mountain found in writing is in the June 30, 1871 edition of The Messenger, in a letter written by civil engineer S. Gilchrist, regarding the engineer's report on the route of the Glen's Falls and Plattsburgh Railroad, from Warrensburg to Chestertown. The earliest reference of the mountain on a map I could find is the 1895 USGS North Creek quadrangle map, where it is incorrectly spelled “Hackenback”; this got corrected on the 1958 edition of this quadrangle.

Hackensack Stone for the Burhans Mansion

The Burhans Mansion, erected in 1865 on the hill behind the present Town Hall for Col. Burhans' son, Frederick O. The stone was quarried from Hackensack Mountain. The property was sold in the early 1960s and eventually the great stone building was torn down. (Source: Warrensburg Heritage Trail, https://www.warrensburgheritagetrail.org/burhans-mansion.html?fbclid=IwAR0zm_X2MA1rIbHioE3736i04xGmuM1Q6rEOTt2WnjiSvy2uVJkW66Zsoeg)

In an article for the Warrensburgh Historical Society Quarterly, John T. Hastings notes that rock from Hackensack was quarried in the past and used to construct various buildings in the town. Hastings writes,

“It is well documented that the construction of the Burhans Mansion was made of cut stone from a ledge on Hackensack Mountain. Albert Alden was the stone mason who, along with the help of tannery workers, built the mansion in the summer of 1865. The stone in the Church of the Holy Cross, Alden's home on Alden Avenue, and the Woodward Block also came from Hackensack Mountain.”

Marie Fisher further elaborates on the history of the Burhans Mansion in an essay on the mansion on the Warrensburg Heritage Trail website:

“Erected in 1865, by Colonel B.P. Burhans for his son, Frederick Burhans, the Italian-villa-style mansion was constructed of native stone, quarried from a ledge on the side of Hackensack Mountain. Albert Alden, of the village, was head mason and the crew was comprised of one hundred-fifty tannery workers from the Burhans' tannery, during the summer suspension of activities at the factory. In quarrying the stone, it was necessary to cut some trees and make a sluiceway down a portion of the mountain, in order to get the big stones to a point where they could be loaded on wagons and stoneboats, to be drawn to the site. Under the guidance of Mr. Alden, many of the tannery workers learned of their fitness for other crafts and, as a result, many did not return to the tannery but went out as experienced carpenters and masons.”

The Burhans' appear to have been prominent members of the Warrensburg community back in the 1800s. The first of this family to settle in Warrensburg is Benjamin Peck Burhans, who came in 1836. A deed record I found from around that time showed he acquired land on much of Hackensack. This historical profile will be updated in the future to elaborate on the legacy of the Burhans family of Warrensburg.

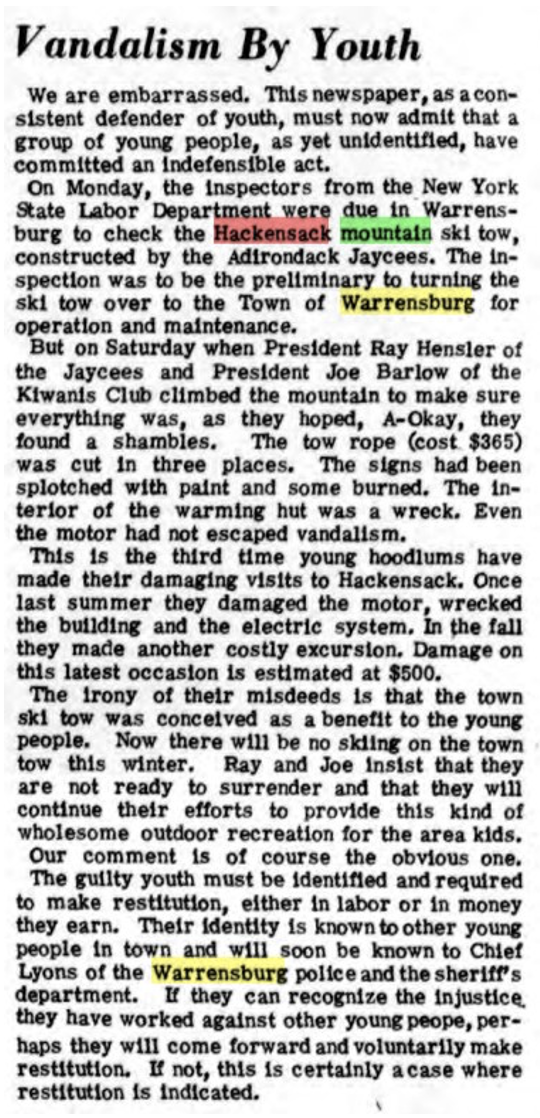

The Blister Hill Ski Slope

Hackensack was also the site for a ski slope called Blister Hill, which was operated by the town from February 22, 1970 until its closure in 1979. According to Jeremy K. Davis, author of Lost Ski Areas of the Southern Adirondacks, Blister Hill was named by Maynard Baker, who had chosen the best name in a contest. A hike of the eastern side of Hackensack will bring one to the remains of the rope tow, which was burned by vandals in 1979. Such vandalism was the nail in the coffin for the Blister Hill ski slope, which never reopened. The ski tow was a victim of vandalism ten years prior, but did not kill the ski operation endeavor on Hackensack.

Papa Boom’s Path

At trailhead at the end of Hackensack Avenue, you will notice a sign for "Papa Boom's Path," named in honor of avid Hackensack climber Tony "Boom" Trapasso. (Credit: John Sasso)

If you start hiking from the trailhead at the end of Hackensack Avenue, you will notice a sign for “Papa Boom's Path,” named in honor of Tony “Boom” Trapasso. According to his obituary, Tony “Boom” Ralph Trapasso was born on September 10, 1960 to Anthony and Evelyn (Atwell) Trapasso, and was a resident of Warrensburg. He received the nickname “Boom” as a boy when he was being tossed in the air by a family friend while the Capital Region radio personality Boom Boom Brannigan was on the radio. Of his mountain climbing, his obituary states:

“Boom was an avid hiker. He hiked many mountains and miles with his long time friend Phil Van Guilder. His favorite mountain, Hackensack Mountain, overlooked his hometown. You could find him hiking Hackensack year round in all kinds of weather. He especially enjoyed hiking when he was accompanied by family and friends. In one year, he climbed Hackensack a total of 277 times. His climbing streak ran 49 consecutive days. Boom’s fastest time to the summit and back was 17 ½ minutes. In his lifetime, he climbed Hackensack 1500 times. The mountain is known to his grandchildren as Papa Boom’s Mountain. If you ascend the mountain, from Hackensack Avenue, you will see a sign displaying his accomplishments at the beginning of the trail. As you climb, you will hike along Papa Boom’s Path and Trapasso Tough Trail.”

Tony Trapasso passed away on January 7, 2022 “after a valiant battle with ALS.”

Other Historical Highlights

View of the American flag near a lookout off the south-facing ridge of Hackensack. (Credit: John Sasso)

Near a lookout off the south-facing ridge of Hackensack you will see an American flag on a pole, something which I have seen for over five years. You can easily see the flag from the hamlet. I do not know any of the history behind this flag, such as who placed it there. If you happen to know, please contact me, John Sasso.

One thing that Hackensack has seen its share of for more than a century is people getting lost on this hill. A simple search on an online newspaper archive reveals dozens of newspaper reports about searches for people lost on Hackensack.

Logging has occurred on Hackensack, primarily on its north-facing side, over more than a century, and as recently as 2011. This historical profile will be updated in the future to elaborate on the history of logging on this peak.

John Sasso is an avid hiker and bushwhacker of the Adirondacks and self-taught Adirondack historian. Outside of his day-job, John manages a Facebook group, History and Legends of the Adirondacks. John also has helped build and maintain trails with the ADK and Adirondack Forty-Sixers, participated in the Trailhead Steward Program, and maintained the fire tower and trail to Mount Adams.

References

“Hackensack Mountain.” Warrensburgh Heritage Trail. https://www.warrensburgheritagetrail.org/hackensack-mountain.html?fbclid=IwAR2sJBpp2o7BOeEOiFTW7zJ9OEa2G7AGSquQ4_ATqRbfxPonvZfHPHzCGj8 (Accessed March 30, 2023)

Jelly-Schapiro, Joshua. Names of New York. Canada: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2021, p. 32.

Beauchamp, William M. “Aboriginal Place Names of New York.” New York State Museum Bulletin 108. Albany, N.Y.: New York State Education Department, 1907.

Trumbull, J. Hammond. The Composition of Indian Geographical names, Illustrated from the Algonkin Languages. Hartford, Ct: Press of Case, Lockwood and Brainard, 1870, p. 30.

Ricky, Donald B. (ed.) Encyclopedia of New Jersey Indians. Vol. 1. St. Clair Shores, MI: Somerset Publishers, Inc., 1998, pp. 115-119.

New Jersey Writers’ Project. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names. Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Public Library Commission, 1945, p. 15.

Nelson, William. The Indians of New Jersey. Patterson, NJ: The Press Printing and Publishing Company, 1894, pp. 102-111.

Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1905, p. 146.

Hodge, Frank W. (ed.) Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Part 2. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1910, p. 1059.

Clark, Patricia R. Tribal Names of the Americas. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2009, p. 78.

Westervelt, Frances A. (ed.) History of Bergen County, New Jersey: 1630-1923. Vol. 1. Chicago, Il: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, Inc., 1923.

Wright, Kevin W. “Native Americans in Bergen County.” Bergen County Historical Society. https://www.bergencountyhistory.org/nativeamericans-in-bergen-county (Accessed March 30, 2023)

Gooding, Barbara J., Sellarole, Terry E., Jones, Theresa E., Petretti, Allan. Hackensack. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

“Burhans Mansion.” Warrensburgh Heritage Trail. https://www.warrensburgheritagetrail.org/burhans-mansion.html(Accessed March 30, 2023)

Hastings, John T. “Between a Rock and a Hard Place.” Warrensburgh Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. 18, Iss. 3, Fall 2013, pp. 1,3-4. http://www.whs12885.org/uploads/5/8/4/4/58449449/whs_newsletter_fall_2013.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0khBsHCPRUBOzZX9NcPMngWMg9Ed4fZ5KeKcRlZgmmyoK98CXz34HdwjQ

Davis, Jeremy K. Lost Ski Areas of the Southern Adirondacks. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012, pp. 56-60.

“Tony Ralph Trapasso” (obituary). Tribute Archive. https://www.tributearchive.com/obituaries/23636703/tony-ralph-trapasso (Accessed March 30, 2023)